A few end-of-the-year thoughts

Another year comes to an end, and along the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline not much has changed. Well there are new mosquito nets, but besides that you will be hard-pressed to find any positive developments for local populations.

The government of Chad continues to collect oil revenues, but apparently is unable to use them to benefit Chadians. Of course the time for believing that the country’s oil wealth would be put to good use is long gone, but it would still be nice to be surprised. With both parliamentary and presidential elections scheduled in 2011, perhaps Deby will decide to put some of the country’s oil money (approximately US$ 5.7 billion earned from project start to July 2010) towards development.

More likely, however, Chad’s oil money will continue financing arms and the military. Deby increased military spending by an astonishing 663 percent between 2000 and 2009, made possible, of course, by oil. And with new Exxon drilling, as well as the Chinese oil projects in the country, there will be plenty of oil money for the foreseeable future.

In Cameroon no one expected the pipeline to bring much wealth to the country (pipeline earnings account for somewhere between 2 and 4% of the Cameroonian budget), and it is unlikely that anyone was waiting for oil money to be spent responsibly. But people hoped, and were assured by the project partners, that the pipeline would not make things worse. Unfortunately, for too many people living along the pipeline, life is harder today than it was before oil arrived.

But there is some encouraging news: the U.S. legislation passed this summer requiring S.E.C. registered extractive industries companies to disclose all payments to governments is an important step towards increased transparency. Transparency is not an end in itself, but is part of an equation that will hold governments accountable and increase the chances that resource revenues are spent wisely. As I said, Chad has elections in 2011 and so does Cameroon (a presidential election in October). Neither Chad nor Cameroon are known for being democratic and there’s no reason to be overly optimistic. However, it’s an interesting moment in the history of “françafrique” and the ongoing electoral crisis in Ivory Coast may very well have implications throughout the region.

Pipeline: Cameroon earns 277.6 million U.S. dollars in seven years

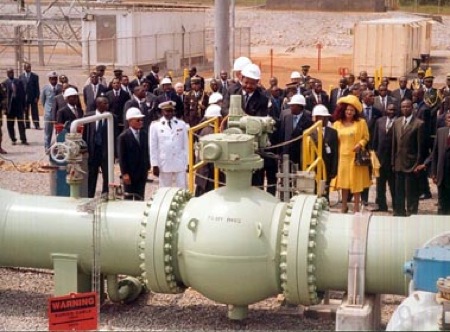

I came across an interesting article that appeared in the Cameroonian daily, Mutations, on December 28th. At a ceremony launching a COTCO-sponsored mosquito net distribution campaign, Guillame Kwelle, the COTCO public and governmental affairs manager, announced that Cameroon had earned nearly US$ 278 million from the pipeline.

Really?

There has been little financial information made available by the Cameroonian government since the pipeline became operational and critics of the project have often pointed to the total lack of transparency regarding Cameroon’s earnings. How much money does the pipeline actually bring in and where does it go? The earnings from the pipeline are part of Cameroon’s petroleum revenues, but there is no data available that would allow people to see what percentage of those revenues comes from the pipeline — as opposed to other oil operations — nor is there any way to know how those revenues are spent. Even if the transit fees are fairly easy to calculate (a fixed, per barrel fee), all the other assorted taxes and fees are harder to estimate. So, this announcement at a COTCO public relations event is newsworthy.

Foreign Aid for Scoundrels

Cameroon’s President Paul Biya, center, with his wife Chantal Biya at a Bastille Day parade on the Champs Elysées, Paris, July 14, 2010. Photo: Orban Thierry/Sipa Press

Foreign Aid for Scoundrels by William Easterly | The New York Review of Books.

William Easterly has written an article in The New York Review of Books that seems fitting for reading on International Anti-Corruption Day. Easterly writes about the “dirty secret” of the international aid system: “Despite much rhetoric to the contrary, the nations and organizations that donate and distribute aid do not care much about democracy and they still actively support dictators. The conventional narrative is that donors supported dictators only during the cold war and ever since have promoted democracy. This is wrong.”

Cameroon and Paul Biya feature prominently in the article. Easterly points out $35 billion in foreign aid during the Biya era have led neither to poverty reduction nor growth in Cameroon. “The average Cameroonian is poorer today than when Biya took power in 1982.”

You can read more by Easterly on the “Aidwatch” blog: http://aidwatchers.com/

Kribi: Major industrial developments on the horizon

Take a nice look at Kribi’s quaint fishing port. It may be unrecognizable in a few years.

After many years of talks and delays, the Cameroonian government appears to be moving ahead with the Kribi deepwater port project, the first step of a major industrial development program.

A recent dispatch from Chinese state radio announced that the Cameroonian government will soon begin a US$50 million compensation program for residents on the site of the future port. According to the article, “The Kribi deep water port in southern Cameroon will be constructed on a 26,000 acres piece of land. It will have an industrial complex with four terminals as well as a mineral wharf for exporting iron. According to the construction timetable, the general excavation works are expected to begin in December.”

No details are provided on the nature of the compensation or the number of people who will be displaced by the project.

The port is not the only major development on the horizon. Work is already underway on Kribi’s gas thermal power plant, which is expected to become operational sometime in late 2012.

Is there a connection between the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline and the proposed industrial development around Kribi? That depends how you define “connection.”

Apathy is not an option

Here’s a post from the ONE BLOG about the International Anti-Corruption Conference getting under way in just a few days in Bangkok. This is a major gathering with more than 1500 people from 130 countries scheduled to attend. I’m thrilled that my short film, Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? will be screening at the conference.

Nov 4th, 2010 4:37 PM EST

By Malaka Gharib

Next week, delegates from more than 130 countries will converge in Bangkok, Thailand to participate in the world’s largest anti-corruption meeting, the 14th annual International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC).

According to Andrew Marshall’s Time Magazine article “How Corruption Is Holding Asia Back,” corruption is a problem that affects dozens of countries across the world — not just developing nations — and has been met with increasing apathy and acceptance from both world leaders and citizens.

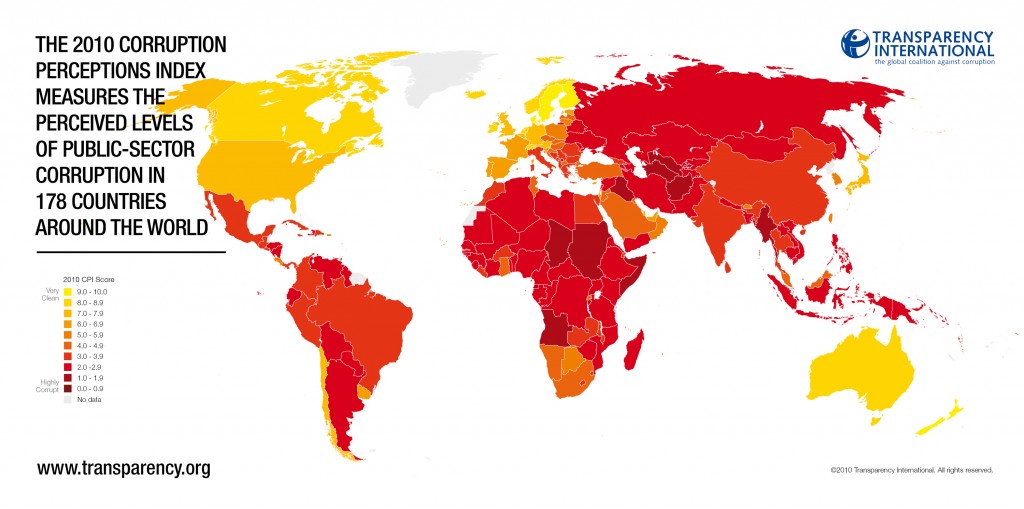

What is most alarming, says Mr. Marshall, is that corruption creates an environment in which dishonesty can thrive even further. Last year’s Transparency International report said that the most common source of bribe demands is the police. And in sub-Saharan Africa, corruption is one of the region’s major barriers to ending extreme poverty. In fact, Africa loses around $148 billion each year as a result of corruption alone.

As you can see, “corruption is everyone’s problem — and apathy is no longer an option,” says Mr. Marshall.

We couldn’t agree more. It’s our duty as advocates to make sure that people know that corruption hurts — not helps — the fight against poverty. We’re curious to see what comes out of this year’s IACC meeting and hope that the delegation makes some headway in this growing issue.

Corruption Index

Transparency International has released its 2010 Corruptions Index. Chad ranks among the ten most corrupt countries in the world. Cameroon has made some progress — just a few years ago the country was at the bottom of the ratings — but is still mired in corruption.

Corruption was a problem in both Chad and Cameroon before Exxon began drilling. Organizations opposed to the World Bank’s involvement in the project warned that rampant corruption would certainly impact any poverty alleviation plans. They were right, but the World Bank knew this, too…which brings us back to the Bank’s crackdown on corruption. You can stop doing business with companies that bribe officials, but as long as those officials operate in a culture of impunity you’re not reducing corruption.

Oil…A Pipeline to Prosperity?

Tourists at Bume Beach, opposite the pipeline's marine loading terminal. Photo by Christiane Badgley

I have produced a short film for PBS/Frontline World to mark the 10th anniversary of World Bank engagement in the Chad-Cameroon Oil Development and Pipeline Project. Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? revisits the story of the “model” oil for development project. Ten years ago the oil companies and the World Bank promised that this project would break the resource curse and prove to the world that oil could be a force for good…

What has happened? Watch the film to see how Chad’s oil has impacted life along the pipeline in Cameroon.

This work was produced with support from Frontline World, The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The Center for Investigative Reporting.

Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? is the first installment in my ongoing exploration of Africa’s booming oil industry, Pipe(line) Dreams. You can read more about the project on the website.

Please support my work on this project by viewing the film and leaving your feedback. It is crucial to show funders that this work matters!

The U.S. now imports more oil from Africa than from the Middle East, with oil accounting for more than 80% of all African imports into the country. African is soon expected to account for close to one quarter of U.S. oil consumption.

With Africa increasingly seen as the next frontier of oil exploration, there is no shortage of oil companies lining up for financing from the World Bank Group. Oil drilling has begun in Ghana with support from the World Bank Group; loans may soon be approved for Uganda. New oil has been found in Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, Angola — even Sierra Leone. The list goes on, with government and corporate officials in each country promising to make oil work for the people.

But in countries lacking accountability, with weak legal systems and lax or nonexistent environmental regulation and enforcement, is oil really a viable development option? And is there a valid reason that public funds subsidize these projects? Both the U.S. and China depend heavily on African oil, yet we rarely see anything about how that oil dramatically transforms African communities, economies and environments. Pipe(line) Dreams, a timely and globally relevant story, will bring much needed attention to the rapidly expanding oil industry in Africa.

Oil Spill near Kribi, Cameroon

A new oil spill was reported at the marine loading terminal offshore from Kribi at 1:45 am on April 22nd.

According to COTCO, the “minor spill” occurred during a violent storm. The transfer of oil from the loading terminal (FSO) to a waiting tanker was halted due to bad weather. High waves washed some “residual oil” from the deck of the waiting tanker. Again, according to COTCO, less than five barrels total were spilled and the oil was immediately cleaned up.

No oil has been reported on the coast, but fishermen did report seeing a sheen of oil offshore.

Several Cameroonian NGOs have released a statement deploring the lack of communication between COTCO and the local populations as well as the lack of any statement or information from the Cameroonian government. The Comité de Pilotage et de Suivi des Pipelines (CPSP), the Cameroonian authority responsible for the pipeline, has not made any public comments regarding the spill. With no information from the government and no journalists allowed near the marine loading terminal, it is extremely difficult to verify COTCO’s information.

In November 2009 the Cameroonian government adopted a national oil spill response plan. This plan, required by the World Bank, should have been in place before oil began to flow along the pipeline in October 2003. The Cameroonian government has not made the plan public and many civil society activists believe the plan remains non-operational. Samuel Nguiffo, from the Center for the Environment and Development, points to the unfolding disaster in the Gulf of Mexico as a warning: “It is urgent that the government increase its capacity to respond to a disaster and make the oil spill response plan operational.”

In the event of a major spill, several million barrels of oil could end up in the Atlantic ocean 12 km. off the coast of Kribi, Cameroon’s main tourist destination and an important fishing and sea turtle nesting zone. The thought of a spill anywhere is terrifying, but watching what’s going on in the Gulf of Mexico now makes me extremely uneasy about Cameroon. Of course the situation in the Gulf is particular, but one clearly sees that controlling an oil spill, even with the best equipment and ample manpower, is incredibly difficult. Any significant spill at the marine loading terminal in Kribi would likely be an ecological (and economic) disaster of major proportions.

It’s important to remember that the offshore marine loading terminal at Kribi (the FSO), is a single-hulled refurbished tanker. Today all tankers, including those used as FSOs, must be double-hulled — an additional protection against spills.

Crude Awakening, Part two

The World Bank-supported Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline looks a lot different on the ground than it does from offices in Washington, D.C. Is the project a success? Depends who you ask!

One thing is certain: the controversy surrounding the “model” oil development project has hardly died down.

This video looks at ongoing compensation problems around Kribi, Cameroon. The Cameroonian Oil Transportation Company, COTCO (ExxonMobil), is responsible for compensating locals for lost lands and revenues.

Traveling from the fishing village of Bumé where locals have been suffering since pipeline construction crews destroyed their fishing grounds, to the Bagyeli pygmy villages in the rainforest, where the Bank-mandated, “Indigenous Peoples’ Plan”, has been stalled for years, I met one angry resident after another.

Today people are especially frustrated as they feel they have no recourse. The government is unresponsive; COTCO (ExxonMobil) is unresponsive. There’s nowhere for people to go with their complaints. It seems the world has forgotten about the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline.

2010 A New Year

Fragile existence. This is the story of life along the pipeline. Whatever happens to the global economy, the price of the barrel or ExxonMobil’s profits in 2010, life here will remain difficult. But the oil won’t stop flowing any time soon and as long as the pipeline is operational, there are opportunities for progress.

Peoples’ voices will be heard, their stories shared. Increased awareness, increased transparency, pressure from stockholders – these are all real possibilities that can lead to change. Oxfam has been actively involved in efforts to promote transparency in the extractive industries, for example, and recently launched a “Follow the Money” campaign. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is moving forward.

Of course any change on the ground will be minimal at best, but let’s all work to make 2010 a year with a bit more social and environmental justice where it’s needed most.

First African President

The town of Campo is located about 80 km (50 miles) south of Kribi, just north of the border with Equatorial Guinea. On paper, the road from Kribi to Campo is paved — it is, after all, an international highway. Of course what’s printed on the map and the reality on the ground are often two very different things. The road, in fact, is unpaved and in terrible condition. At the end of the rainy season the drive from Kribi to Campo took longer than three hours. Along the way we encountered several big trucks stuck in the mud, their drivers sitting on the roadside. They were waiting for the sun to dry the mud enough for the trucks to move again. A wait that could last several days…

For me Campo was a stop on the road to the Campo Ma’an National Park. To access the park by land, you have to travel another two and a half hours east along what used to be a logging road. Now it’s more of a path, barely wide enough for a car to pass. The forest ranger who accompanied us to the park said that on average the road gets used once every two months, just enough to keep the forest from completely reclaiming the land.

At the last settlement before the park entrance, we encountered a Bagyeli man in an Obama t-shirt. “The first African president,” he said. Obama t-shirts weren’t unusual; I also saw a few cars, buses — even bars — named Obama. But this t-shirt was special. It was so worn and so far from any town or city; it really seemed to sum up the symbolic importance of Obama here. The first African president.

Now with 2010 just around the corner, let’s remember Obama’s declaration: “Africa doesn’t need strongmen. It needs strong institutions.” He pronounced those words in July while in Ghana. I hope that in this coming year Obama will be more than the symbolic first African president, that he will take actions to show his commitment to the continent and its peoples is real.

Missing Fish

Fishing in Kribi isn’t what it used to be. There are certainly multiple reasons for the decline in fish stock, but everyone here singles out the pipeline as the main culprit. The pipeline cuts right through the middle of the coastal village of Bume, just south of Kribi, on its way to the marine loading terminal 12 kilometers offshore. The residents of Bumé, who depend entirely on fishing, blame the pipeline for killing their livelihood.

There are two types of fishing in the Kribi area and the pipeline impacted each differently. The hardest hit are the small, village fisherman — like the residents of Bumé — who put their nets out just offshore. These fishermen do not have motor power; they paddle their small dugout canoes out to sea and are unable work more than a few kilometers from shore.

They used to catch the fish that lived in the reef just offshore. That reef was blasted away during pipeline construction and the fish have never come back. Using their traditional fishing methods, local fishermen now pull in only a few kilos of fish at a time. Sometimes, they pull in nothing at all.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, the initial pipeline plans did not include the destruction of the reef. As no one from ExxonMobil would speak to me, I could not find out why this, a significant environmental impact, was not not part of any early reviews. The shallow waters of the coast here are lined with rocky offshore reefs and the Bumé reef was clearly visible. If any local fishermen had been interviewed, they would have talked about the importance of the reef for local fishing.

C is for Corruption

This is an angry man. He’s standing in a 4 million CFCA (US$ 9000) fish pond. Well, it was supposed to be a fish pond.

When the last section of the pipeline was laid from the beach at Kribi to the offshore marine loading terminal, construction crews blasted away the reef at Bumé, the fishing village at “ground zero.” The fish left the area and for the population of Bumé, entirely dependent on fishing, this was a disaster.

The original pipeline plans did not include the reef’s destruction, so there was no mitigation plan in place when the crews came through. After much discussion, the consortium offered to construct two ponds for fish farming. Never mind that the villagers of Bumé are fisherman, not fish farmers, and that they have neither the skills nor the resources for aquaculture. These artisanal fishermen paddle out with their nets out once or twice a day, catching relatively small amounts of fish in the shallow waters. This is subsistence fishing: they bring in just enough to eat and, if all goes well, sell a few fish each day.

La Saveur

I can’t spend all my time writing about the pipeline or I’ll end up depressed. There’s lots to talk about in Cameroon…and one thing I can’t resist is the food. Cameroonian food is delicious. I say it’s the best in Africa. Of course, I should say it’s the best African cuisine I know, but I don’t think I’ll find better.

Cameroon has some 250 ethnic groups, each with its special dishes, and that alone makes for an extremely varied cuisine. Then, there’s such an abundance of great ingredients: the markets are jammed with a vast array of vegetables, fruits, grains, nuts, beans, tubers, peppers, spices — a profusion of colors and perfumes. Cameroon produces coffee, tea and chocolate. Fishermen bring in a variety of fish, seafood and shellfish everyday.

What’s a Tree Worth?

Godefroy Edzoa is the traditional chief of Ekabita. The pipeline crosses straight through the fields of Ekabita where people grow cocoa, avocados, mangoes, safou, papayas, and a variety of crops including bananas, corn, cassava, squash and peanuts.

Edzoa tells me that when the pipeline people came to Ekabita, they told residents there would be compensation for damaged crops. They also said that once the pipeline construction was completed, residents could farm their lands again. However, no fruit trees could be planted on the 30-meter wide easement, as tree roots could damage the pipeline. Farmers were told that the easement would be cleared several times a year, probably after harvests, but were given no firm details. Even today farmers can not tell me exactly when the easement will be cleared, as the calendar seems to change each year.

Deby’s Surprise Visit

The President of Chad, Idriss Deby, made a surprise visit to Yaounde on October 28th. As the visit was announced only 24 hours before Deby’s arrival, the private press was full of speculation on what urgent matter brought Deby to Cameroon.

Officially, Biya and Deby held a short, private meeting to discuss bilateral cooperation and the receding waters of Lake Chad, an item that both countries will bring up at the Copenhagen climate conference. Unofficially, the corruption scandal at the Bank of Central African States, in which a Chadian minister may be implicated, as well as the renegotiation of pipeline contracts, could have been items for discussion.

Pipeline Dreaming

What happens when a major American oil company comes through two poor African countries with a project to drill for oil in one and transport it across the other?

Dreams. Fantasies. Unrealistic expectations. False hopes. As Samuel Nguiffo, founder of the Center for the Environment and Development in Yaounde told me, “People hear oil, America, dollars, jobs. They hear it’s a 25-year project. From there it becomes money and jobs for everyone for 25 years.”

Langue de bois

I’ve been in Cameroon for a week now, and there’s lots to talk about. I have to begin, though, with my efforts to get anyone connected with the pipeline project to speak to me. As I’ve been spending many hours in waiting rooms, I felt that this photo kind of summed up a good part of my week.

“Langue de bois” is a French expression: literally, a wooden tongue. Cliches. Hackneyed phrases. Spin. Waffle. What politicians and business leaders do when they want to talk without saying anything, avoid answering difficult questions, steer our attention away from unpleasant subjects, etc.

“As you can imagine, ExxonMobil receives many worthwhile requests from news organizations for interviews. Unfortunately, it is impossible to respond affirmatively to all these requests. Due to timing and other business constraints, representatives of Esso Chad will not be available to participate in the opportunity you present. However, for information, I’ve enclosed a case study of the project, as well as a 2008 news release that notes the benefits of the project.”

En route

Here I am watching the Paris drizzle from terminal 2C at Charles de Gaulle airport, waiting for my flight to Douala. After months of discussions and proposal writing and waiting for the rainy season to (almost) end, I’m finally off to Cameroon.

Here I am watching the Paris drizzle from terminal 2C at Charles de Gaulle airport, waiting for my flight to Douala. After months of discussions and proposal writing and waiting for the rainy season to (almost) end, I’m finally off to Cameroon.

My plan is to eventually travel the length of the pipeline, to see up-close how this project has really affected people in Chad and Cameroon. On this first trip, I’ll explore the last 250 kilometers of the pipeline, a section that passes close to Yaoundé, the capital of Cameroon, and then continues through the rainforest to the town of Kribi, on the Atlantic coast.

The forest between Yaoundé and Kribi is home to the Bagyeli, one of Cameroon’s two pygmy populations. The World Bank and the ExxonMobil-led consortium were convinced the pipeline project would help the Bagyeli. As part of the mitigation process, the pipeline consortium established an indigenous peoples’ foundation to run health and education programs for the Bagyeli. Many environmentalists and civil society activists, on the other hand, feared that the pipeline would disrupt the Bagyeli’s already fragile existence. As many Bagyeli continue to rely on the forest for their food and their livelihoods, any damage to the local ecosystem could be devastating.

This is one story that I’ll be looking at in the coming weeks.

But now, it’s boarding time.

Paradise and the Pipeline

Kribi. It could be paradise. The small beach town on Cameroon’s Atlantic coast is one of the country’s prime tourist attractions. The dense rainforest stretches almost to the water’s edge; a strip of white sand beach is all that separates the greens of the forest from the turquoise waters. Just south of town the famous Lobé waterfalls tumble over black volcanic rocks directly into the ocean. Market women sell and prepare fish right off the boats at the town’s small port.

The first time I visited Kribi was in December, 1994, and the beauty of the place was stunning. Of course, most of the town was rundown and ramshackle. Electricity ran intermittently and the water was not fit to drink. Unfortunately this was (and is) the story of much of Cameroon. But Kribi managed somehow to have a certain charm and people spoke proudly of their little corner of paradise.