2011: Oil will lead economic growth in Africa

For better or for worse…

It’s January 1st and it seems fitting to post this piece from the “beyond brics” blog at the Financial Times.

What slowdown? Oil to drive growth

December 17, 2010 10:42 am by Henry Mance

For the global economy, Christmas parties came early this year: stimulus spending boosted growth to possibly unsustainable rates. Next year, a mild hangover is likely to kick in – with slower growth in much of the world, including China, India and Brazil.

Yet, for those in need of some more festive cheer, there are three regions that are forecast to see faster growth in 2011: the Middle East and North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, and Russia and central Asia. All three will average at least 4.6 per cent growth, according to the IMF, overtaking Latin America as the world’s most dynamic regions after Developing Asia. Why are they accelerating? The common thread is oil.

Pipeline: Cameroon earns 277.6 million U.S. dollars in seven years

I came across an interesting article that appeared in the Cameroonian daily, Mutations, on December 28th. At a ceremony launching a COTCO-sponsored mosquito net distribution campaign, Guillame Kwelle, the COTCO public and governmental affairs manager, announced that Cameroon had earned nearly US$ 278 million from the pipeline.

Really?

There has been little financial information made available by the Cameroonian government since the pipeline became operational and critics of the project have often pointed to the total lack of transparency regarding Cameroon’s earnings. How much money does the pipeline actually bring in and where does it go? The earnings from the pipeline are part of Cameroon’s petroleum revenues, but there is no data available that would allow people to see what percentage of those revenues comes from the pipeline — as opposed to other oil operations — nor is there any way to know how those revenues are spent. Even if the transit fees are fairly easy to calculate (a fixed, per barrel fee), all the other assorted taxes and fees are harder to estimate. So, this announcement at a COTCO public relations event is newsworthy.

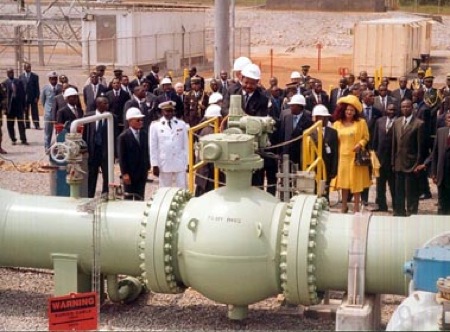

OIL: Africa’s pipeline to prosperity?

Ian Gary, Senior Policy Manager for Extractive Industries at Oxfam America, joined me at Amherst College on December 8th for a screening and discussion on Africa’s oil challenges. Gary, who co-authored, Chad’s Oil: Miracle or Mirage? in 2005, reminded us that Africa’s oil boom will provide more that $400 billion to African governments through 2019. By 2015 the U.S. will get 25% of its imported oil from Africa.

Chad’s oil, to the surprise of no-one really, has hardly worked miracles. The country is no better off than it was before oil production began. Most economic indicators are down. The people in the oil-producing region are much worse off than they were before the oil boom. Farmers for the most part, many in the Doba Basin area are no longer able to access their lands, now dotted with drill pads and crossed by pipes and high tension cables. In 2010, the World Bank admitted that “in reality, close to 50 percent of expenditures has gone to the military.”

Chad, once the “model” for oil development (although one can argue that Chad was only a “model” until oil began to flow), has now joined the ranks of examples to avoid. The resource curse strikes again. Ghana is next, with its first oil shipping on December 15th. Will Ghana go the way of Chad or will the country get it right this time? Although the Ghanaian government has made pledges and promises, recent news suggests that there is some cause for concern (read a few of the latest articles posted on Ghana Oil Watch to get a sense of the troubles on the horizon).

WikiLeaks cables: Shell’s grip on Nigerian state revealed

I am posting an article from The Guardian. This news is a stark reminder that the “resource curse,” is not just a problem of bad governance and corrupt politicians.

The oil giant Shell claimed it had inserted staff into all the main ministries of the Nigerian government, giving it access to politicians’ every move in the oil-rich Niger Delta, according to a leaked US diplomatic cable.

The company’s top executive in Nigeria told US diplomats that Shell had seconded employees to every relevant department and so knew “everything that was being done in those ministries”. She boasted that the Nigerian government had “forgotten” about the extent of Shell’s infiltration and was unaware of how much the company knew about its deliberations.

The cache of secret dispatches from Washington’s embassies in Africa also revealed that the Anglo-Dutch oil firm swapped intelligence with the US, in one case providing US diplomats with the names of Nigerian politicians it suspected of supporting militant activity, and requesting information from the US on whether the militants had acquired anti-aircraft missiles….

Campaigners tonight said the revelation about Shell in Nigeria demonstrated the tangled links between the oil firm and politicians in the country where, despite billions of dollars in oil revenue, 70% of people live below the poverty line.

Deja vu all over again

In a few weeks Ghana’s first oil will ship and lately the news coming from Accra has been less than encouraging. There’s been a lot of talk the past few years about making oil revenues work for the Ghanaian people (with references to avoiding Chad’s problems), but now that the country is moving from talk to action there’s cause for concern.

Kribi: Major industrial developments on the horizon

Take a nice look at Kribi’s quaint fishing port. It may be unrecognizable in a few years.

After many years of talks and delays, the Cameroonian government appears to be moving ahead with the Kribi deepwater port project, the first step of a major industrial development program.

A recent dispatch from Chinese state radio announced that the Cameroonian government will soon begin a US$50 million compensation program for residents on the site of the future port. According to the article, “The Kribi deep water port in southern Cameroon will be constructed on a 26,000 acres piece of land. It will have an industrial complex with four terminals as well as a mineral wharf for exporting iron. According to the construction timetable, the general excavation works are expected to begin in December.”

No details are provided on the nature of the compensation or the number of people who will be displaced by the project.

The port is not the only major development on the horizon. Work is already underway on Kribi’s gas thermal power plant, which is expected to become operational sometime in late 2012.

Is there a connection between the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline and the proposed industrial development around Kribi? That depends how you define “connection.”

The recurring question

Oil, an opportunity for economic development or a curse for African countries? That question is the subject of a recent radio panel on RFI (Radio France Internationale). It’s a two-part feature, in French. One of the invited guests, Gerard Magrin, is a Chad specialist who has written about southern Chad’s transition from cotton fields to oil fields.

Oil, an opportunity for economic development or a curse for African countries? That question is the subject of a recent radio panel on RFI (Radio France Internationale). It’s a two-part feature, in French. One of the invited guests, Gerard Magrin, is a Chad specialist who has written about southern Chad’s transition from cotton fields to oil fields.

You can listen to the discussion here:

Here’s a link to the second half of the discussion:

http://www.rfi.fr/emission/20101114-2-debat-le-petrole-opportunites-developpement-malediction-pays-africains

Speaking of farming, the subsistence farmers of Chad would have certainly benefited from an end to U.S. subsidies for American cotton farmers. Instead they got oil. That’s “development”. You can read more about how U.S. subsidies hurt African cotton growers in a recent Guardian article, “The Great Cotton Stitch-Up”.

Apathy is not an option

Here’s a post from the ONE BLOG about the International Anti-Corruption Conference getting under way in just a few days in Bangkok. This is a major gathering with more than 1500 people from 130 countries scheduled to attend. I’m thrilled that my short film, Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? will be screening at the conference.

Nov 4th, 2010 4:37 PM EST

By Malaka Gharib

Next week, delegates from more than 130 countries will converge in Bangkok, Thailand to participate in the world’s largest anti-corruption meeting, the 14th annual International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC).

According to Andrew Marshall’s Time Magazine article “How Corruption Is Holding Asia Back,” corruption is a problem that affects dozens of countries across the world — not just developing nations — and has been met with increasing apathy and acceptance from both world leaders and citizens.

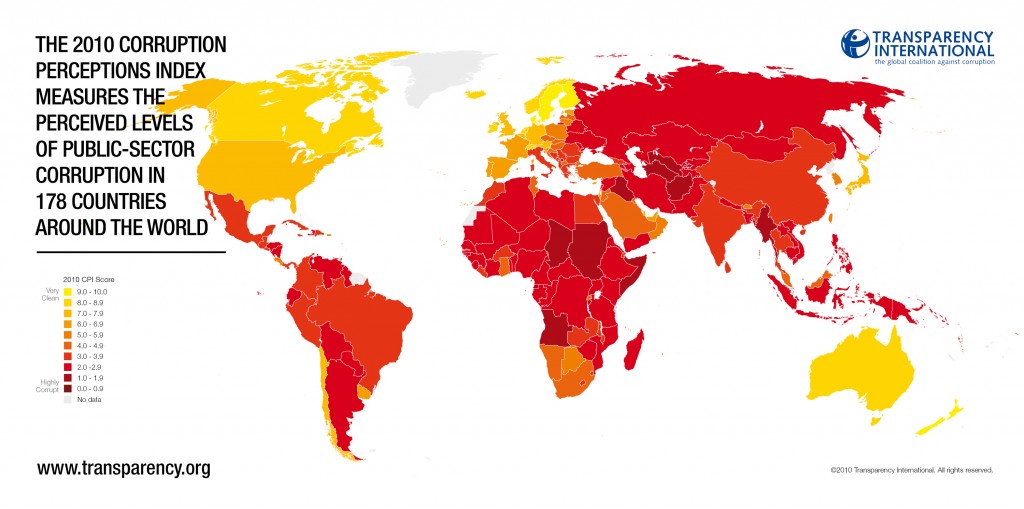

What is most alarming, says Mr. Marshall, is that corruption creates an environment in which dishonesty can thrive even further. Last year’s Transparency International report said that the most common source of bribe demands is the police. And in sub-Saharan Africa, corruption is one of the region’s major barriers to ending extreme poverty. In fact, Africa loses around $148 billion each year as a result of corruption alone.

As you can see, “corruption is everyone’s problem — and apathy is no longer an option,” says Mr. Marshall.

We couldn’t agree more. It’s our duty as advocates to make sure that people know that corruption hurts — not helps — the fight against poverty. We’re curious to see what comes out of this year’s IACC meeting and hope that the delegation makes some headway in this growing issue.

Corruption Index

Transparency International has released its 2010 Corruptions Index. Chad ranks among the ten most corrupt countries in the world. Cameroon has made some progress — just a few years ago the country was at the bottom of the ratings — but is still mired in corruption.

Corruption was a problem in both Chad and Cameroon before Exxon began drilling. Organizations opposed to the World Bank’s involvement in the project warned that rampant corruption would certainly impact any poverty alleviation plans. They were right, but the World Bank knew this, too…which brings us back to the Bank’s crackdown on corruption. You can stop doing business with companies that bribe officials, but as long as those officials operate in a culture of impunity you’re not reducing corruption.

Licence to probe: World Bank trains its sights on corruption crackdown

This is significant news from the World Bank so I’m posting the entire Guardian article below. I tend to agree with the author’s assessment: this is an important step in the right direction, but there’s a long, long way to go. I’m looking into non-compliance on aspects of the loan agreements with Chad and Cameroon that have not been effectively enforced. Avoiding obligations—with no apparent consequences—is not corruption. But it certainly doesn’t help advance the rule of law. And what better for corruption than a culture of impunity? I’ll be posting more about this soon.

Article by Larry Elliott, guardian.co.uk, October 8 2010

The World Bank’s latest anti-corruption initiative may sound a bit Bond, but it shows issues like fraud and bribery are being taken seriously. Photograph: Reuters

It will have 250 staff operating out of 150 countries and sounds like Ian Fleming dreamed it up. Yet the International Corruption Hunters Network (ICHN) is not something out of a James Bond novel, but the World Bank‘s latest initiative for stamping out bribery, fraud and the pilfering of money designed to alleviate poverty.

The idea is a good one. There are countless individual agencies around the world dedicated to stamping out financial crime: pooling their expertise should make it more difficult for the venal to get away with it. And not before time, since the taxpayers who last year provided the $70bn-plus spent by the World Bank in the field need to know that their money is not finding its way into numbered Swiss bank accounts or swelling the profits of unscrupulous companies.

Oil…A Pipeline to Prosperity?

Tourists at Bume Beach, opposite the pipeline's marine loading terminal. Photo by Christiane Badgley

I have produced a short film for PBS/Frontline World to mark the 10th anniversary of World Bank engagement in the Chad-Cameroon Oil Development and Pipeline Project. Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? revisits the story of the “model” oil for development project. Ten years ago the oil companies and the World Bank promised that this project would break the resource curse and prove to the world that oil could be a force for good…

What has happened? Watch the film to see how Chad’s oil has impacted life along the pipeline in Cameroon.

This work was produced with support from Frontline World, The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The Center for Investigative Reporting.

Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? is the first installment in my ongoing exploration of Africa’s booming oil industry, Pipe(line) Dreams. You can read more about the project on the website.

Please support my work on this project by viewing the film and leaving your feedback. It is crucial to show funders that this work matters!

The U.S. now imports more oil from Africa than from the Middle East, with oil accounting for more than 80% of all African imports into the country. African is soon expected to account for close to one quarter of U.S. oil consumption.

With Africa increasingly seen as the next frontier of oil exploration, there is no shortage of oil companies lining up for financing from the World Bank Group. Oil drilling has begun in Ghana with support from the World Bank Group; loans may soon be approved for Uganda. New oil has been found in Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, Angola — even Sierra Leone. The list goes on, with government and corporate officials in each country promising to make oil work for the people.

But in countries lacking accountability, with weak legal systems and lax or nonexistent environmental regulation and enforcement, is oil really a viable development option? And is there a valid reason that public funds subsidize these projects? Both the U.S. and China depend heavily on African oil, yet we rarely see anything about how that oil dramatically transforms African communities, economies and environments. Pipe(line) Dreams, a timely and globally relevant story, will bring much needed attention to the rapidly expanding oil industry in Africa.

Nigeria’s agony dwarfs the Gulf oil spill. The US and Europe ignore it.

The Deepwater Horizon disaster caused headlines around the world, yet the people who live in the Niger delta have had to live with environmental catastrophes for decades.

John Vidal, environment editor, The Observer, Sunday 30 May 2010

We reached the edge of the oil spill near the Nigerian village of Otuegwe after a long hike through cassava plantations. Ahead of us lay swamp. We waded into the warm tropical water and began swimming, cameras and notebooks held above our heads. We could smell the oil long before we saw it – the stench of garage forecourts and rotting vegetation hanging thickly in the air.

The farther we travelled, the more nauseous it became. Soon we were swimming in pools of light Nigerian crude, the best-quality oil in the world. One of the many hundreds of 40-year-old pipelines that crisscross the Niger delta had corroded and spewed oil for several months.

Forest and farmland were now covered in a sheen of greasy oil. Drinking wells were polluted and people were distraught. No one knew how much oil had leaked. “We lost our nets, huts and fishing pots,” said Chief Promise, village leader of Otuegwe and our guide. “This is where we fished and farmed. We have lost our forest. We told Shell of the spill within days, but they did nothing for six months.”

That was the Niger delta a few years ago, where, according to Nigerian academics, writers and environment groups, oil companies have acted with such impunity and recklessness that much of the region has been devastated by leaks.

In fact, more oil is spilled from the delta’s network of terminals, pipes, pumping stations and oil platforms every year than has been lost in the Gulf of Mexico, the site of a major ecological catastrophe caused by oil that has poured from a leak triggered by the explosion that wrecked BP‘s Deepwater Horizon rig last month.

The Yes Men Inspire Nigerian Activists

The Yes Lab has helped Nigerian activists pull off a successful hoax. Here’s the story:

Shell Flummoxed by Fakers

Company flummoxes back; activist group takes responsibility

The Hague – Hours before Shell’s annual general shareholder meeting on Tuesday, and not long after BP’s oil rig catastrophe, millions of people around the world received press releases announcing that Shell would implement a “comprehensive remediation plan” for the oil-soaked Niger Delta. The plan included an immediate halt to dangerous offshore drilling, the end of health-damaging gas flaring, and reparations for the human damage caused over the decades of Shell’s involvement.

The “good news” was fiction, created by an ad-hoc activist group called the Nigerian Justice League to generate pressure on Shell to withdraw from, and remediate, the Niger Delta. According to the activists, Shell’s operations in the Delta have helped transform that area into the world’s most polluted ecosystem, which has in turn resulted in a human rights catastrophe.

(The NJL developed the project as part of the Yes Lab, a workshop run by a group called “The Yes Men” to share their experiences and facilitate the projects of others. The Yes Lab is in the midst of a fundraising drive.)

“Shell, Chevron, and the others are perpetrating a massive, life-threatening hoax by claiming that they can’t quickly stop their gas flaring, reduce their oil spills, and clean up their mess in the Niger Delta,” said Chris Francis of the Nigerian Justice League. “Our press release revealed the truth: that there is a decent way forward, instead of the continual deceit we get from them.”

Shell’s public relations staff quickly and energetically moved to contain the fallout from the fake release. On Tuesday, Shell attempted to eliminate the Justice League’s spoof Shell website by complaining that it was a “phishing scheme” to the upstream internet service provider. Shell then sent a threatening legal letter to the Danish internet provider hosting the site.

In a related story, the Financial Times (a blog of which, incidentally, was duped by the fake release) refused to run a hard-hitting advertisement, created and paid for by Amnesty International, that called for action against Shell for its Niger Delta legacy. Like the fake release, the ad was timed to coincide with Shell’s May 18 AGM.

“For now, Shell’s legal threats are bearing ripe fruit,” said Esmée de la Parra of the Nigerian Justice League. “But they can’t keep blustering their way to destruction forever. Eventually, people will have had enough. For the sake of the planet, let’s hope ‘eventually’ is very soon.”

Self regulating?

Here’s a worrisome bit of reporting from the New York Times: “Regulator Lets the Industry Call the Shots on Safety.” Eric Lipton and John Broder report that the Minerals Management Service and the Interior Department never took the actions necessary to impose backup systems to control the giant undersea valves known as blowout preventers. This despite numerous spills and repeated warnings about the necessity of such measures over more than a decade.

The article continues with a list of oversights, safety violations and government passes for the industry. Again, I wonder about Africa. Who is regulating drilling operations and enforcing those regulations in West-Central Africa?

Deepwater Drilling

I just came across this highly informative post, “Deepwater Drilling — What Can go Wrong?” on the Ghanaian blog, CROSSED CROCODILES.

Check it out. The unfolding disaster in the Gulf of Mexico is indeed a cautionary tale for Africa. Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ghana… deepwater drilling is happening or on the horizon in a number of countries.

Despite the massive efforts of the oil companies and state and federal authorities, the situation in the Gulf of Mexico is spinning out of control. The thought of a similar accident occurring off the coast of West or Central Africa is terrifying.

Oil Spill near Kribi, Cameroon

A new oil spill was reported at the marine loading terminal offshore from Kribi at 1:45 am on April 22nd.

According to COTCO, the “minor spill” occurred during a violent storm. The transfer of oil from the loading terminal (FSO) to a waiting tanker was halted due to bad weather. High waves washed some “residual oil” from the deck of the waiting tanker. Again, according to COTCO, less than five barrels total were spilled and the oil was immediately cleaned up.

No oil has been reported on the coast, but fishermen did report seeing a sheen of oil offshore.

Several Cameroonian NGOs have released a statement deploring the lack of communication between COTCO and the local populations as well as the lack of any statement or information from the Cameroonian government. The Comité de Pilotage et de Suivi des Pipelines (CPSP), the Cameroonian authority responsible for the pipeline, has not made any public comments regarding the spill. With no information from the government and no journalists allowed near the marine loading terminal, it is extremely difficult to verify COTCO’s information.

In November 2009 the Cameroonian government adopted a national oil spill response plan. This plan, required by the World Bank, should have been in place before oil began to flow along the pipeline in October 2003. The Cameroonian government has not made the plan public and many civil society activists believe the plan remains non-operational. Samuel Nguiffo, from the Center for the Environment and Development, points to the unfolding disaster in the Gulf of Mexico as a warning: “It is urgent that the government increase its capacity to respond to a disaster and make the oil spill response plan operational.”

In the event of a major spill, several million barrels of oil could end up in the Atlantic ocean 12 km. off the coast of Kribi, Cameroon’s main tourist destination and an important fishing and sea turtle nesting zone. The thought of a spill anywhere is terrifying, but watching what’s going on in the Gulf of Mexico now makes me extremely uneasy about Cameroon. Of course the situation in the Gulf is particular, but one clearly sees that controlling an oil spill, even with the best equipment and ample manpower, is incredibly difficult. Any significant spill at the marine loading terminal in Kribi would likely be an ecological (and economic) disaster of major proportions.

It’s important to remember that the offshore marine loading terminal at Kribi (the FSO), is a single-hulled refurbished tanker. Today all tankers, including those used as FSOs, must be double-hulled — an additional protection against spills.

Mini update: News from Chad

Happier days…

I haven’t posted anything in a while, as I’m in the midst of editing. I’ll post more material soon. In the meantime, here’s some news from the recent IMF staff mission to Chad (March 4-17):

“Economic activity remained sluggish in 2009, but inflation increased further, owing to food prices. Low rainfall, and therefore agricultural output, plus the trend decline in oil production led to a contraction in real GDP of about 2 percent. The bad harvest could imply food shortage for up to 2 million people (18 percent of the population). The need for additional food is estimated at between 80,000 to 100,000 metric tons, for which the government has requested external assistance.

“The global financial crisis affected Chad mainly through the ensuing decline in oil prices. The fiscal position deteriorated sharply in 2009 to a deficit of about 20 percent of non-oil GDP as the government maintained spending levels in the face of a fall-off in oil revenues by almost depleting its oil savings and borrowing from the central bank…Overspending on security and investment in 2009 absorbed an important part of the resources that had been lined up to finance the 2010 budget.”

Hardly looks good. Chad remains desperately poor, 18% of the population risks going hungry and the government can’t pay its bills. All this despite the benefits that oil brought to the country.

Money in, money out. I think this is what economists’ call the “resource curse”, you know, what wasn’t going to happen this time…

Crude Awakening, Part two

The World Bank-supported Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline looks a lot different on the ground than it does from offices in Washington, D.C. Is the project a success? Depends who you ask!

One thing is certain: the controversy surrounding the “model” oil development project has hardly died down.

This video looks at ongoing compensation problems around Kribi, Cameroon. The Cameroonian Oil Transportation Company, COTCO (ExxonMobil), is responsible for compensating locals for lost lands and revenues.

Traveling from the fishing village of Bumé where locals have been suffering since pipeline construction crews destroyed their fishing grounds, to the Bagyeli pygmy villages in the rainforest, where the Bank-mandated, “Indigenous Peoples’ Plan”, has been stalled for years, I met one angry resident after another.

Today people are especially frustrated as they feel they have no recourse. The government is unresponsive; COTCO (ExxonMobil) is unresponsive. There’s nowhere for people to go with their complaints. It seems the world has forgotten about the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline.

News from Washington

I’ve recently returned from Washington, D.C., where I was able to interview World Bank and other officials about the Chad-Cameroon Oil Development Project.

Very interesting…

I’m now editing some video sequences and will post material soon.

2010 A New Year

Fragile existence. This is the story of life along the pipeline. Whatever happens to the global economy, the price of the barrel or ExxonMobil’s profits in 2010, life here will remain difficult. But the oil won’t stop flowing any time soon and as long as the pipeline is operational, there are opportunities for progress.

Peoples’ voices will be heard, their stories shared. Increased awareness, increased transparency, pressure from stockholders – these are all real possibilities that can lead to change. Oxfam has been actively involved in efforts to promote transparency in the extractive industries, for example, and recently launched a “Follow the Money” campaign. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is moving forward.

Of course any change on the ground will be minimal at best, but let’s all work to make 2010 a year with a bit more social and environmental justice where it’s needed most.

First African President

The town of Campo is located about 80 km (50 miles) south of Kribi, just north of the border with Equatorial Guinea. On paper, the road from Kribi to Campo is paved — it is, after all, an international highway. Of course what’s printed on the map and the reality on the ground are often two very different things. The road, in fact, is unpaved and in terrible condition. At the end of the rainy season the drive from Kribi to Campo took longer than three hours. Along the way we encountered several big trucks stuck in the mud, their drivers sitting on the roadside. They were waiting for the sun to dry the mud enough for the trucks to move again. A wait that could last several days…

For me Campo was a stop on the road to the Campo Ma’an National Park. To access the park by land, you have to travel another two and a half hours east along what used to be a logging road. Now it’s more of a path, barely wide enough for a car to pass. The forest ranger who accompanied us to the park said that on average the road gets used once every two months, just enough to keep the forest from completely reclaiming the land.

At the last settlement before the park entrance, we encountered a Bagyeli man in an Obama t-shirt. “The first African president,” he said. Obama t-shirts weren’t unusual; I also saw a few cars, buses — even bars — named Obama. But this t-shirt was special. It was so worn and so far from any town or city; it really seemed to sum up the symbolic importance of Obama here. The first African president.

Now with 2010 just around the corner, let’s remember Obama’s declaration: “Africa doesn’t need strongmen. It needs strong institutions.” He pronounced those words in July while in Ghana. I hope that in this coming year Obama will be more than the symbolic first African president, that he will take actions to show his commitment to the continent and its peoples is real.

Missing Fish

Fishing in Kribi isn’t what it used to be. There are certainly multiple reasons for the decline in fish stock, but everyone here singles out the pipeline as the main culprit. The pipeline cuts right through the middle of the coastal village of Bume, just south of Kribi, on its way to the marine loading terminal 12 kilometers offshore. The residents of Bumé, who depend entirely on fishing, blame the pipeline for killing their livelihood.

There are two types of fishing in the Kribi area and the pipeline impacted each differently. The hardest hit are the small, village fisherman — like the residents of Bumé — who put their nets out just offshore. These fishermen do not have motor power; they paddle their small dugout canoes out to sea and are unable work more than a few kilometers from shore.

They used to catch the fish that lived in the reef just offshore. That reef was blasted away during pipeline construction and the fish have never come back. Using their traditional fishing methods, local fishermen now pull in only a few kilos of fish at a time. Sometimes, they pull in nothing at all.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, the initial pipeline plans did not include the destruction of the reef. As no one from ExxonMobil would speak to me, I could not find out why this, a significant environmental impact, was not not part of any early reviews. The shallow waters of the coast here are lined with rocky offshore reefs and the Bumé reef was clearly visible. If any local fishermen had been interviewed, they would have talked about the importance of the reef for local fishing.

C is for Corruption

This is an angry man. He’s standing in a 4 million CFCA (US$ 9000) fish pond. Well, it was supposed to be a fish pond.

When the last section of the pipeline was laid from the beach at Kribi to the offshore marine loading terminal, construction crews blasted away the reef at Bumé, the fishing village at “ground zero.” The fish left the area and for the population of Bumé, entirely dependent on fishing, this was a disaster.

The original pipeline plans did not include the reef’s destruction, so there was no mitigation plan in place when the crews came through. After much discussion, the consortium offered to construct two ponds for fish farming. Never mind that the villagers of Bumé are fisherman, not fish farmers, and that they have neither the skills nor the resources for aquaculture. These artisanal fishermen paddle out with their nets out once or twice a day, catching relatively small amounts of fish in the shallow waters. This is subsistence fishing: they bring in just enough to eat and, if all goes well, sell a few fish each day.

La Saveur

I can’t spend all my time writing about the pipeline or I’ll end up depressed. There’s lots to talk about in Cameroon…and one thing I can’t resist is the food. Cameroonian food is delicious. I say it’s the best in Africa. Of course, I should say it’s the best African cuisine I know, but I don’t think I’ll find better.

Cameroon has some 250 ethnic groups, each with its special dishes, and that alone makes for an extremely varied cuisine. Then, there’s such an abundance of great ingredients: the markets are jammed with a vast array of vegetables, fruits, grains, nuts, beans, tubers, peppers, spices — a profusion of colors and perfumes. Cameroon produces coffee, tea and chocolate. Fishermen bring in a variety of fish, seafood and shellfish everyday.