Better late than never: Cameroon renegotiates pipeline transit fees

After ten years of operations, Cameroon has finally managed to renegotiate the paltry transit fees it collects on the Chad-Cameroon pipeline.

Cameroon will now receive 618.02 CFA francs ($1.30) per barrel of oil, up from 194.91 CFA francs. Since 2003 Cameroon was collecting less than U.S. 45 cents per barrel, a rate that was not linked to inflation or to the price of oil. Nor was the rate subject to regular review. Even the current rate, $1.30 per barrel, is low, but it will at least be raised every five years based on the rate of inflation.

The quantity of oil coming down the pipeline will soon increase as Niger has signed an agreement to use the pipeline. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), the operator in Niger, will also use the pipeline for its Chadian operations. Exxon Mobil has not disclosed how much CNPC will pay to use the pipeline.

Read more:

Pipeline Tchad-Cameroun: Le droit de passage passe de 194 FCFA à 618 FCFA par baril

Niger awards second oil permit to CNPC, plans exports

Another Exxon Mobil pipeline ruptures

Exxon Mobil pipeline problems are back in the news and this time it’s in Arkansas.

From InsideClimate News: A pipeline that ruptured and leaked at least 80,000 gallons of oil into central Arkansas on Friday was transporting a heavy form of crude from the Canadian tar sands region, ExxonMobil told InsideClimate News.

Local police said the line gushed oil for 45 minutes before being stopped, according to media reports.

Crude oil ran through a subdivision of Mayflower, Ark., about 20 miles north of Little Rock. Twenty-two homes were evacuated, but no one was hospitalized, Exxon spokesman Charlie Engelmann said on Saturday.

In an interview with InsideClimate News, Faulkner County Judge Allen Dodson said emergency crews prevented the oil from entering waterways. The judge issued an emergency declaration following the spill and is involved in coordinating clean-up efforts among federal, state and local agencies and Exxon.

Pipeline news

Although the work I’m doing now in Cameroon is not directly related to the Chad-Cameroon pipeline, I’m getting updates on the pipeline as possible.

Last week I had a meeting at the Ministry of the Environment and Conservation and learned that Cameroon is once again trying to renegotiate the transit fees it receives for pipeline use. Although most of the pipeline is in Cameroon, which means that most of the environmental risk is in Cameroon, the country benefits only minimally from the operation. Most of Cameroon’s revenues from the project come in the form of transit fees collected on the oil pumped through the pipeline. Even at the time of signing, the rate (41 cents per barrel) was low and to add insult to injury, the transit fee isn’t indexed to inflation or to the cost of oil.

In the nine years that the pipeline has been operational, Cameroon has watched the price of oil skyrocket while its meager transit fees have remained unchanged. (See my December 2010 post on the lack of transparency surrounding Cameroon’s earnings from the pipeline.)

New pipeline safety report: Much room for improvement

Vulnerable to dangerous spills: The Chad-Cameroon pipeline crosses a number of rivers in remote, densely forested areas. Photo: Christiane Badgley

The New York Times Green Blog reports on a new pipeline study from the U.S. National Wildlife Federation (NWF).

Times reporter Dan Frosch writes that the NWF study, “asserts that federal laws regulating oil pipelines are inadequate in several crucial areas and that local regulations do not provide sufficient protection against safety and environmental risks.”

The NWF report was prompted by a July 2010 rupture of an Enbridge Energy Partners oil pipeline in Michigan that spilled some 1 million gallons of crude oil, contaminating more than 30 miles of a major Lake Michigan truibutary. According to NWF, the incident, “raised health concerns and killed wildlife. It also exposed numerous weaknesses in pipeline regulation.

Pipeline oversight: Are independent monitoring panels effective, truly independent?

Over the past few weeks I’ve been scrutinizing documents on the safety and oversight of the Chad-Cameroon pipeline. As I wrote in an initial blog post, the ruptured ExxonMobil pipeline and subsequent oil spill in the Yellowstone River in Montana got me thinking about similarities with the ExxonMobil pipeline that crosses no fewer than 17 major rivers in Cameroon. I then wrote a follow-up post on pipeline oversight (or lack of).

So I was thrilled when I found out that Oxfam America was preparing a new report on the monitoring of controversial oil and gas projects featuring the Chad-Cameroon pipeline as one of its case studies. The report, Watching the Watchdogs, was launched yesterday in Washington, D.C. Among the speakers at yesterday’s panel were Jacques Gérin and Nadji Nelambaye who were both involved with monitoring the Chad-Cameroon pipeline.

Pipelines: More on the Montana – Cameroon connection

Farmer Jean Edzoa standing on the pipeline easement near Yaounde. He and other farmers in the area complain that "nothing grows" around the pipeline. Photo by Christiane Badgley

I recently wrote about ExxonMobil’s July oil spill in Montana and what lessons the Yellowstone River accident may have for Cameroon.

The same day an article in The New York Times, Pipeline Spills Put Safeguards Under Scrutiny, analyzed the regulation and oversight of the 167,000-mile system of hazardous liquid pipelines crisscrossing the United States.

The article describes a federal monitoring agency that is, “chronically short of inspectors and lacks the resources needed to hire more, leaving too much of the regulatory control in the hands of pipeline operators themselves…”

Exxon spill in Montana: lessons for Cameroon?

A member of the Blackfeet Tribe takes 'water' samples for a community hospital water lab near Cut Bank Creek, Mont. Photo: Destini Vaile/AP

On July 1 an ExxonMobil underground pipeline ruptured near Laurel, Montana, spilling tens of thousands of gallons of crude oil into the Yellowstone River. Montana is a long way from Africa, but this spill has me thinking about the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline, another ExxonMobil underground pipeline that passes below several rivers where water pressure and erosion are real concerns.

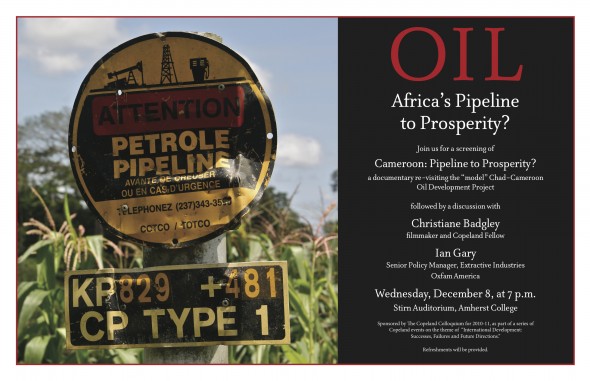

The 30 meter wide pipeline easement is supposed to be kept cleared at all times. This pipeline marker was buried under thick brush in clear violation of safety regulations. Photo by Christiane Badgley

Environmentalists in Cameroon and Chad have long been concerned about the safety of the 1070 km Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline and have stated repeatedly that COTCO (ExxonMobil pipeline operations in Cameroon) has not provided reliable information about its real capacity to respond in the event of an oil spill. Much of the pipeline crosses relatively remote and hard-to-access areas (few or no roads) and many question COTCO’s assertions that response teams could quickly travel to the scene of any incident.

It’s been awhile…

Days turn into weeks and I haven’t posted a thing. I guess I’ve got those oil blues…

Well, that and I have been editing video and preparing an article for publication. If all goes as planned, new material should be online in the next few days. I’ve also been to London to interview Stuart Wheaton, Ghana Development Manager for Tullow Oil, and Romain Chancerel, Project Manager for the Global Initiative for West and Central Africa (GIWACAF). GIWACAF is a public-private partnership working to develop and enhance oil spill response capacity in the Gulf of Guinea region.

Will the Chinese use the Chad-Cameroon pipeline?

I just stumbled across an interesting bit of news. China and ExxonMobil may do business together in Chad. I said, “may,” not “will,” but this could be a significant development.

It is fascinating the way information about the Chad-Cameroon pipeline is revealed. It’s really difficult to get interviews with government or oil company officials. I’ve tried off and on for months, to no avail. So for some information I watch what comes through the (state-run) press. Nothing is straightforward. Items often appear about events that occurred months earlier, for seemingly no reason, but sometimes interesting little nuggets of information are mentioned in passing.

If you’re not paying attention, they are easily overlooked. For example, a few days ago, the Cameroon Tribune (government publication) ran an article about the pipeline with the headline, “36.75 million barrels of oil and 7.6 billion Francs” (That’s about US$ 17 million.)

The article, basically highlights from the October 2010 Pipeline Steering and Monitoring Committee report, began with details on the quantity of oil that had transited across Cameroon during the first ten months of 2010, along with information on the transit fees. Apparently less oil was pumped in 2010 than in 2009. Okay. Chances are if you weren’t following the pipeline story you wouldn’t even read beyond the headline.

Yet, several paragraphs down, the article contained some intriguing information.

A few end-of-the-year thoughts

Another year comes to an end, and along the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline not much has changed. Well there are new mosquito nets, but besides that you will be hard-pressed to find any positive developments for local populations.

The government of Chad continues to collect oil revenues, but apparently is unable to use them to benefit Chadians. Of course the time for believing that the country’s oil wealth would be put to good use is long gone, but it would still be nice to be surprised. With both parliamentary and presidential elections scheduled in 2011, perhaps Deby will decide to put some of the country’s oil money (approximately US$ 5.7 billion earned from project start to July 2010) towards development.

More likely, however, Chad’s oil money will continue financing arms and the military. Deby increased military spending by an astonishing 663 percent between 2000 and 2009, made possible, of course, by oil. And with new Exxon drilling, as well as the Chinese oil projects in the country, there will be plenty of oil money for the foreseeable future.

In Cameroon no one expected the pipeline to bring much wealth to the country (pipeline earnings account for somewhere between 2 and 4% of the Cameroonian budget), and it is unlikely that anyone was waiting for oil money to be spent responsibly. But people hoped, and were assured by the project partners, that the pipeline would not make things worse. Unfortunately, for too many people living along the pipeline, life is harder today than it was before oil arrived.

But there is some encouraging news: the U.S. legislation passed this summer requiring S.E.C. registered extractive industries companies to disclose all payments to governments is an important step towards increased transparency. Transparency is not an end in itself, but is part of an equation that will hold governments accountable and increase the chances that resource revenues are spent wisely. As I said, Chad has elections in 2011 and so does Cameroon (a presidential election in October). Neither Chad nor Cameroon are known for being democratic and there’s no reason to be overly optimistic. However, it’s an interesting moment in the history of “françafrique” and the ongoing electoral crisis in Ivory Coast may very well have implications throughout the region.

Pipeline: Cameroon earns 277.6 million U.S. dollars in seven years

I came across an interesting article that appeared in the Cameroonian daily, Mutations, on December 28th. At a ceremony launching a COTCO-sponsored mosquito net distribution campaign, Guillame Kwelle, the COTCO public and governmental affairs manager, announced that Cameroon had earned nearly US$ 278 million from the pipeline.

Really?

There has been little financial information made available by the Cameroonian government since the pipeline became operational and critics of the project have often pointed to the total lack of transparency regarding Cameroon’s earnings. How much money does the pipeline actually bring in and where does it go? The earnings from the pipeline are part of Cameroon’s petroleum revenues, but there is no data available that would allow people to see what percentage of those revenues comes from the pipeline — as opposed to other oil operations — nor is there any way to know how those revenues are spent. Even if the transit fees are fairly easy to calculate (a fixed, per barrel fee), all the other assorted taxes and fees are harder to estimate. So, this announcement at a COTCO public relations event is newsworthy.

OIL: Africa’s pipeline to prosperity?

Ian Gary, Senior Policy Manager for Extractive Industries at Oxfam America, joined me at Amherst College on December 8th for a screening and discussion on Africa’s oil challenges. Gary, who co-authored, Chad’s Oil: Miracle or Mirage? in 2005, reminded us that Africa’s oil boom will provide more that $400 billion to African governments through 2019. By 2015 the U.S. will get 25% of its imported oil from Africa.

Chad’s oil, to the surprise of no-one really, has hardly worked miracles. The country is no better off than it was before oil production began. Most economic indicators are down. The people in the oil-producing region are much worse off than they were before the oil boom. Farmers for the most part, many in the Doba Basin area are no longer able to access their lands, now dotted with drill pads and crossed by pipes and high tension cables. In 2010, the World Bank admitted that “in reality, close to 50 percent of expenditures has gone to the military.”

Chad, once the “model” for oil development (although one can argue that Chad was only a “model” until oil began to flow), has now joined the ranks of examples to avoid. The resource curse strikes again. Ghana is next, with its first oil shipping on December 15th. Will Ghana go the way of Chad or will the country get it right this time? Although the Ghanaian government has made pledges and promises, recent news suggests that there is some cause for concern (read a few of the latest articles posted on Ghana Oil Watch to get a sense of the troubles on the horizon).

Kribi: Major industrial developments on the horizon

Take a nice look at Kribi’s quaint fishing port. It may be unrecognizable in a few years.

After many years of talks and delays, the Cameroonian government appears to be moving ahead with the Kribi deepwater port project, the first step of a major industrial development program.

A recent dispatch from Chinese state radio announced that the Cameroonian government will soon begin a US$50 million compensation program for residents on the site of the future port. According to the article, “The Kribi deep water port in southern Cameroon will be constructed on a 26,000 acres piece of land. It will have an industrial complex with four terminals as well as a mineral wharf for exporting iron. According to the construction timetable, the general excavation works are expected to begin in December.”

No details are provided on the nature of the compensation or the number of people who will be displaced by the project.

The port is not the only major development on the horizon. Work is already underway on Kribi’s gas thermal power plant, which is expected to become operational sometime in late 2012.

Is there a connection between the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline and the proposed industrial development around Kribi? That depends how you define “connection.”

I’m back…

The marine loading terminal (FSO), photo by Christiane Badgley

It has been quite awhile, but I’m back to work on Pipe(line) Dreams. I’ll post new video soon along with some updates and oil news.

Oil…A Pipeline to Prosperity?

Tourists at Bume Beach, opposite the pipeline's marine loading terminal. Photo by Christiane Badgley

I have produced a short film for PBS/Frontline World to mark the 10th anniversary of World Bank engagement in the Chad-Cameroon Oil Development and Pipeline Project. Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? revisits the story of the “model” oil for development project. Ten years ago the oil companies and the World Bank promised that this project would break the resource curse and prove to the world that oil could be a force for good…

What has happened? Watch the film to see how Chad’s oil has impacted life along the pipeline in Cameroon.

This work was produced with support from Frontline World, The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and The Center for Investigative Reporting.

Cameroon: Pipeline to Prosperity? is the first installment in my ongoing exploration of Africa’s booming oil industry, Pipe(line) Dreams. You can read more about the project on the website.

Please support my work on this project by viewing the film and leaving your feedback. It is crucial to show funders that this work matters!

The U.S. now imports more oil from Africa than from the Middle East, with oil accounting for more than 80% of all African imports into the country. African is soon expected to account for close to one quarter of U.S. oil consumption.

With Africa increasingly seen as the next frontier of oil exploration, there is no shortage of oil companies lining up for financing from the World Bank Group. Oil drilling has begun in Ghana with support from the World Bank Group; loans may soon be approved for Uganda. New oil has been found in Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, Angola — even Sierra Leone. The list goes on, with government and corporate officials in each country promising to make oil work for the people.

But in countries lacking accountability, with weak legal systems and lax or nonexistent environmental regulation and enforcement, is oil really a viable development option? And is there a valid reason that public funds subsidize these projects? Both the U.S. and China depend heavily on African oil, yet we rarely see anything about how that oil dramatically transforms African communities, economies and environments. Pipe(line) Dreams, a timely and globally relevant story, will bring much needed attention to the rapidly expanding oil industry in Africa.

Nigeria’s agony dwarfs the Gulf oil spill. The US and Europe ignore it.

The Deepwater Horizon disaster caused headlines around the world, yet the people who live in the Niger delta have had to live with environmental catastrophes for decades.

John Vidal, environment editor, The Observer, Sunday 30 May 2010

We reached the edge of the oil spill near the Nigerian village of Otuegwe after a long hike through cassava plantations. Ahead of us lay swamp. We waded into the warm tropical water and began swimming, cameras and notebooks held above our heads. We could smell the oil long before we saw it – the stench of garage forecourts and rotting vegetation hanging thickly in the air.

The farther we travelled, the more nauseous it became. Soon we were swimming in pools of light Nigerian crude, the best-quality oil in the world. One of the many hundreds of 40-year-old pipelines that crisscross the Niger delta had corroded and spewed oil for several months.

Forest and farmland were now covered in a sheen of greasy oil. Drinking wells were polluted and people were distraught. No one knew how much oil had leaked. “We lost our nets, huts and fishing pots,” said Chief Promise, village leader of Otuegwe and our guide. “This is where we fished and farmed. We have lost our forest. We told Shell of the spill within days, but they did nothing for six months.”

That was the Niger delta a few years ago, where, according to Nigerian academics, writers and environment groups, oil companies have acted with such impunity and recklessness that much of the region has been devastated by leaks.

In fact, more oil is spilled from the delta’s network of terminals, pipes, pumping stations and oil platforms every year than has been lost in the Gulf of Mexico, the site of a major ecological catastrophe caused by oil that has poured from a leak triggered by the explosion that wrecked BP‘s Deepwater Horizon rig last month.

Oil Spill near Kribi, Cameroon

A new oil spill was reported at the marine loading terminal offshore from Kribi at 1:45 am on April 22nd.

According to COTCO, the “minor spill” occurred during a violent storm. The transfer of oil from the loading terminal (FSO) to a waiting tanker was halted due to bad weather. High waves washed some “residual oil” from the deck of the waiting tanker. Again, according to COTCO, less than five barrels total were spilled and the oil was immediately cleaned up.

No oil has been reported on the coast, but fishermen did report seeing a sheen of oil offshore.

Several Cameroonian NGOs have released a statement deploring the lack of communication between COTCO and the local populations as well as the lack of any statement or information from the Cameroonian government. The Comité de Pilotage et de Suivi des Pipelines (CPSP), the Cameroonian authority responsible for the pipeline, has not made any public comments regarding the spill. With no information from the government and no journalists allowed near the marine loading terminal, it is extremely difficult to verify COTCO’s information.

In November 2009 the Cameroonian government adopted a national oil spill response plan. This plan, required by the World Bank, should have been in place before oil began to flow along the pipeline in October 2003. The Cameroonian government has not made the plan public and many civil society activists believe the plan remains non-operational. Samuel Nguiffo, from the Center for the Environment and Development, points to the unfolding disaster in the Gulf of Mexico as a warning: “It is urgent that the government increase its capacity to respond to a disaster and make the oil spill response plan operational.”

In the event of a major spill, several million barrels of oil could end up in the Atlantic ocean 12 km. off the coast of Kribi, Cameroon’s main tourist destination and an important fishing and sea turtle nesting zone. The thought of a spill anywhere is terrifying, but watching what’s going on in the Gulf of Mexico now makes me extremely uneasy about Cameroon. Of course the situation in the Gulf is particular, but one clearly sees that controlling an oil spill, even with the best equipment and ample manpower, is incredibly difficult. Any significant spill at the marine loading terminal in Kribi would likely be an ecological (and economic) disaster of major proportions.

It’s important to remember that the offshore marine loading terminal at Kribi (the FSO), is a single-hulled refurbished tanker. Today all tankers, including those used as FSOs, must be double-hulled — an additional protection against spills.

2010 A New Year

Fragile existence. This is the story of life along the pipeline. Whatever happens to the global economy, the price of the barrel or ExxonMobil’s profits in 2010, life here will remain difficult. But the oil won’t stop flowing any time soon and as long as the pipeline is operational, there are opportunities for progress.

Peoples’ voices will be heard, their stories shared. Increased awareness, increased transparency, pressure from stockholders – these are all real possibilities that can lead to change. Oxfam has been actively involved in efforts to promote transparency in the extractive industries, for example, and recently launched a “Follow the Money” campaign. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is moving forward.

Of course any change on the ground will be minimal at best, but let’s all work to make 2010 a year with a bit more social and environmental justice where it’s needed most.

A new article on the Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline

I read a strong piece today on AlterNet, A Humanitarian Disaster in the Making Along the Chad-Cameroon Oil Pipeline — Who’s Watching?, written by Brendan Schwartz and Valery Nodem who I recently had a chance to meet in Yaoundé.

The article provides an excellent summary of much of what’s wrong with the Chad-Cameroon oil pipeline… and describes many of the ongoing issues that prompted me to begin work on the Pipe(line) Dreams project.

Missing Fish

Fishing in Kribi isn’t what it used to be. There are certainly multiple reasons for the decline in fish stock, but everyone here singles out the pipeline as the main culprit. The pipeline cuts right through the middle of the coastal village of Bume, just south of Kribi, on its way to the marine loading terminal 12 kilometers offshore. The residents of Bumé, who depend entirely on fishing, blame the pipeline for killing their livelihood.

There are two types of fishing in the Kribi area and the pipeline impacted each differently. The hardest hit are the small, village fisherman — like the residents of Bumé — who put their nets out just offshore. These fishermen do not have motor power; they paddle their small dugout canoes out to sea and are unable work more than a few kilometers from shore.

They used to catch the fish that lived in the reef just offshore. That reef was blasted away during pipeline construction and the fish have never come back. Using their traditional fishing methods, local fishermen now pull in only a few kilos of fish at a time. Sometimes, they pull in nothing at all.

As I mentioned in an earlier post, the initial pipeline plans did not include the destruction of the reef. As no one from ExxonMobil would speak to me, I could not find out why this, a significant environmental impact, was not not part of any early reviews. The shallow waters of the coast here are lined with rocky offshore reefs and the Bumé reef was clearly visible. If any local fishermen had been interviewed, they would have talked about the importance of the reef for local fishing.

What’s a Tree Worth?

Godefroy Edzoa is the traditional chief of Ekabita. The pipeline crosses straight through the fields of Ekabita where people grow cocoa, avocados, mangoes, safou, papayas, and a variety of crops including bananas, corn, cassava, squash and peanuts.

Edzoa tells me that when the pipeline people came to Ekabita, they told residents there would be compensation for damaged crops. They also said that once the pipeline construction was completed, residents could farm their lands again. However, no fruit trees could be planted on the 30-meter wide easement, as tree roots could damage the pipeline. Farmers were told that the easement would be cleared several times a year, probably after harvests, but were given no firm details. Even today farmers can not tell me exactly when the easement will be cleared, as the calendar seems to change each year.

Deby’s Surprise Visit

The President of Chad, Idriss Deby, made a surprise visit to Yaounde on October 28th. As the visit was announced only 24 hours before Deby’s arrival, the private press was full of speculation on what urgent matter brought Deby to Cameroon.

Officially, Biya and Deby held a short, private meeting to discuss bilateral cooperation and the receding waters of Lake Chad, an item that both countries will bring up at the Copenhagen climate conference. Unofficially, the corruption scandal at the Bank of Central African States, in which a Chadian minister may be implicated, as well as the renegotiation of pipeline contracts, could have been items for discussion.

Pipeline Dreaming

What happens when a major American oil company comes through two poor African countries with a project to drill for oil in one and transport it across the other?

Dreams. Fantasies. Unrealistic expectations. False hopes. As Samuel Nguiffo, founder of the Center for the Environment and Development in Yaounde told me, “People hear oil, America, dollars, jobs. They hear it’s a 25-year project. From there it becomes money and jobs for everyone for 25 years.”

Langue de bois

I’ve been in Cameroon for a week now, and there’s lots to talk about. I have to begin, though, with my efforts to get anyone connected with the pipeline project to speak to me. As I’ve been spending many hours in waiting rooms, I felt that this photo kind of summed up a good part of my week.

“Langue de bois” is a French expression: literally, a wooden tongue. Cliches. Hackneyed phrases. Spin. Waffle. What politicians and business leaders do when they want to talk without saying anything, avoid answering difficult questions, steer our attention away from unpleasant subjects, etc.

“As you can imagine, ExxonMobil receives many worthwhile requests from news organizations for interviews. Unfortunately, it is impossible to respond affirmatively to all these requests. Due to timing and other business constraints, representatives of Esso Chad will not be available to participate in the opportunity you present. However, for information, I’ve enclosed a case study of the project, as well as a 2008 news release that notes the benefits of the project.”